Miami 1980 / Baltimore 2015

By John Dorschner

Has anything really changed?

Thirty-five years ago, on May 17, 1980, Miami fell apart in the McDuffie riots. State and federal panels demanded profound changes be made to improve poor black neighborhoods. Local leaders vowed to do it. The question today: Has there been substantial change?

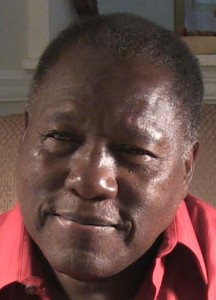

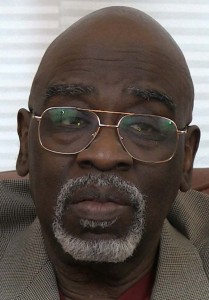

“The answer is essentially no,” says Marvin Dunn, co-author of The Miami Riot of 1980 and a retired Florida International University professor. “We could publish the same recommendations today and they would be just as relevant. We could just box them up and send them to Baltimore without additional commentary. It’s typical. Have a problem, get a group of citizens together and as soon as the cameras leave and the reporters go home, things become muddled again.”

Dunn is marking the 35th anniversary of the riots by campaigning for the city of Miami to place an historic marker at the spot where black motorcyclist Arthur McDuffie was killed during an encounter with police. The location is on the edge of the Design District, near Miami Avenue and North 38th Street, by the entrance ramp to State Road 112.

“That spot changed Miami history,” Dunn says.

Baltimore, of course, is where poor blacks recently rioted after a black man died in police custody. The Baltimore days of rage have spawned a new flurry of highly critical examination – not only of the behavior of the justice system, but also the conditions in the poor Baltimore neighborhood where intense poverty and high unemployment has existed for decades.

Both Baltimore and Miami involved the eruption of poor neighborhoods angered at the death of an unarmed black man in the hands of police. No one was killed during the Baltimore disturbances. Eighteen died in Miami on May 17, 18 and 19, 1980, as black mobs pulled white motorists from cars and beat them.

What tumultuous days those were. That May, tens of thousands of Cubans rushed to South Florida from Mariel, overwhelming local governments. Meanwhile, a Tampa jury found four county cops not guilty of killing McDuffie. The riots caused at least $100 million in property damage.

The Mariel influx was gradually absorbed in Miami – increasing the area’s south-looking focus in ways still continuing – but the aftermath of the riots is another story.

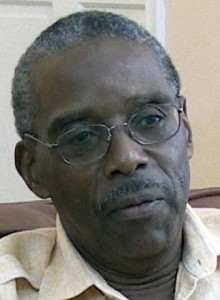

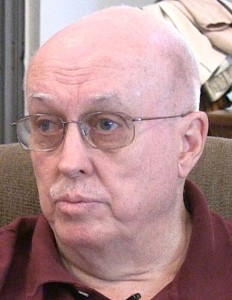

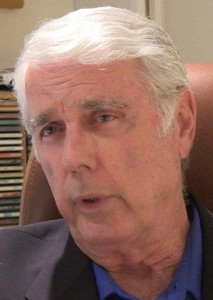

Dunn and several other persons who were major players in Miami 1980 (including retired Judge Tom Petersen, former police chief Ken Harms, Herald columnist Joe Oglesby and former county police spokesman Lonnie Lawrence) see little or no improvement in the poor areas of Miami.

They all see similarities (and some differences) in the festering situation in Baltimore.

Their discussions have two main themes: Police treatment of blacks and the dismal poverty in the riot areas. Miami leaders generally believe they’re related issues, but they must be dealt with separately: Pouring money into public housing doesn’t fix police-black relations.

Dunn puts it this way: Affluent blacks are no more likely to riot than affluent whites. But if poor blacks rioted only because of bad economic conditions, “the country would be in a constant state of riot. In short, injustice caused the riot, not economic problems.”

FIXING POOR BLACK AREAS

Nonetheless, much of the soul-searching in Miami (as in Baltimore) focused on the grinding social problems in the poor black areas.

The 1980 riots spurred two major studies.

A Governor’s Citizens Committee said Liberty City was likely to explode even without the McDuffie verdict, and problems urgently needed to be fixed: wretched housing conditions, “functional illiteracy,” inadequate youth recreational facilities, “hard-core juvenile delinquents,” an unfair criminal justice system and “political deprivation.”

In 1982, the U.S. Civil Rights Commission, after lengthy hearings, filed an 188-page report: Confronting Racial Isolation in Miami. It decried poverty, lack of job opportunities (especially for youth), along with problems in the criminal justice system. The report said “greater commitment .. on the part of all levels of government and the private sector in Miami will be required to make meaningful in that city our Nation’s promise of equality for all.”

Jimmy Carter, president in 1980, had vowed to rebuild Liberty City. The feds ultimately promised $116 million for the project. A 1985 study by the U.S. General Accounting Office found $70.6 million had been spent, but that included items such as $8 million to develop rapid transit – a service that later studies showed helped much more the affluent southern suburbs than the poor northern areas.

Only $43 million went directly to the riot areas, and that included $17 million to small businesses damaged in the riots. That program, however, didn’t require that the businesses rebuild in Liberty City and many rebuilt elsewhere.

Joe Oglesby, retired editor of The Miami Herald’s editorial page, says that in many ways Liberty City is “worse today than it was before the riots in 1980.”

Before, the area had “a fair number of middle class,” people who moved out after the riots. “And the businesses are not there. There’s some economic activity – government offices, FPL’s office – but Northside Shopping Center is worse today than it was then. It’s almost a flea market. Major retailers are gone.”

Lonnie Lawrence, who in 1980 was the spokesman for county police, says: “I don’t think a lot’s been done in Liberty City. Some places burned down are still vacant lots.”

Tom Petersen also wonders how much has changed. A onetime chief assistant of Janet Reno, he spent several years studying the problems of public housing projects and went on to become a juvenile judge. He asks now how much has improved from the basic report of the Civil Rights Commission report, that blacks were isolated and excluded from opportunity and mobility.

“I would expect substantial improvement,” Petersen wrote in a recent email, “but riding through Liberty City my thought would be that we are a long way from economic parity.”

In fact, census numbers on the heart of Liberty City show little change. Data for census tract 15.01 – Liberty Square housing project and nearby streets show that between 1980 and 2013 American Community Survey estimates, underlying poverty and segregation continues to fester.

Population has shrunk – from 4,944 in 1980 to 3,709 in 2013. In 1980, the area was 99.3 percent black. In 2013, it was 93.2 percent, a change thanks a small influx of Hispanics, including 77 Hondurans.

Like 1980, the area is mostly women (two-thirds of those aged 20-64) and a third are children under 15.

Education has improved considerably. In 1980, two-thirds of those over 25 didn’t have a high school degree. The 2013 census estimate is that roughly quarter of adults the area didn’t have a degree. Gisela Feild, administrative director for assessment, research and data analysis for Dade schools, says that, thanks to system anti-dropout programs, there’s been a steady trend in recent years for higher percentage of kids graduating.

But for this census tract, more high school diplomas doesn’t necessarily mean better income. In 1980, 56.5 percent of families were below the poverty line. In 2013, using a slightly different measurement 47.4 percent of those over 15 were mired in poverty.

Unemployment in 2013 was 46.8 percent. (In 1980, the census said the tract’s unemployment was 11.4 percent, but that would be based on persons seeking work and not finding it, and only 40 percent of adults listed themselves in 1980 as being in the labor force.)

A JUVENILE SYSTEM WITH SAME PROBLEMS

Petersen, the longtime juvenile judge, says the handling of troubled kids, a focus of the 1982 Civil Rights Commission report, “in virtually all respects … could be written today.”

He cites examples from the 1982 report:

♦ The proportion of black youths in the juvenile system is three times as great as their proportion of the population.

♦ The lack of adequate neighborhood recreation programs.

♦ “The Dade juvenile justice system has not deterred juvenile crime effectively.”

♦ 83% of black youths in the system come from one-parent households and 65% from poverty level homes.

♦ By its failure to intervene effectively, the juvenile justice system reinforces and perpetuates the process of discrimination that has fostered black juvenile delinquency.

Petersen concludes: “The persistence of these negative outcomes, in my judgment, is the result of the system’s continuing to see the cause of delinquent crime as being psychological – attributable to the individual youth’s psyche – as opposed to external sociological factors such as dysfunctional neighborhoods and ineffective schools which result in high dropout rates and the consequent strong influence of a negative peer culture.

“ Judge Bill Gladstone is quoted in the report as saying ‘The fault doesn’t lie with the system. It lies with the community that produced the kids that come into the system.‘ I agree with that,” writes Petersen. “To a remarkable extent the neighborhoods from which the great majority of felony delinquent youths come are not significantly different than the same neighborhoods 35 years ago.”

Petersen goes on: “Bob Simms [then director of the Dade Community Relations Board], quoted in the report makes an obvious and accurate observation: ‘It is perceived that there is unequal treatment of enforcement to the black community, especially in certain enforcement jurisdictions. Whether this is true or not does not necessarily matter. It is perceived to be that way. Therefore, for the perceiver, I suspect that is the truth.’

“That statement,” Petersen writes in an email, “is accurate now as it was in 1980, we need look no further than Ferguson, Staten Island, Charleston and all of the other incidents that differ from 1980 only in that none of them has generated a riot/disturbance such as the McDuffie incident generated 35 years ago.”

THE POLICE PROBLEMS

White cops killing black unarmed citizens – it happened in Miami in 1980 and, in recent months, it’s happened in Ferguson, Staten Island, Charleston and Baltimore. Each incident sparked outrage. In Ferguson and Staten Island, grand juries saw no reason to indict. In Charleston, the officer was charged because video showed he shot a fleeing man.

In Baltimore, crowds celebrated when the prosecutor quickly indicted six cops, but there were celebrations too in Miami when prosecutors indicted six cops in 1980 – celebrations that turned to riots when the cops were acquitted. The Miami black community – and many white political leaders – were shocked by the verdicts, but recent interviews with one prosecutor and four defense attorneys reveal that the state had huge problems with its case and the public shouldn’t have been surprised. The Baltimore prosecutions are just beginning, but many studies show that it’s not easy to convince juries to convict police officers.

One issue is the racial-ethnic makeup of the police force. In Ferguson, in particular, the cops were overwhelmingly white while the vast majority of residents were black.

In Miami 1980, the county cops – called then the Public Safety Department, the group that employed all the indicted McDuffie officers – had eight percent black officers at a time when 15 percent of county residents were black. Very few blacks were in positions of authority. Non-Hispanic whites dominated both the force and the leadership.

That’s changed hugely. Miami-Dade police are now led by a black director. As of the April human resources report, one in five officers – 20.16 percent – are black. That’s more that the 20.05 percent who are white non-Hispanic. Hispanics are now 58.6 percent. All those percentages are close to mirroring the county’s population.

HOW TO IMPROVE POLICE PERFORMANCE

Having a representative police force is important, virtually everyone agrees. But is that enough?

Dunn, the retired professor, says that after the eruption at Ferguson, “I’m just one- half step away from recommending black police officers for black neighborhoods.”

Many commentators have discussed the almost Pavlovian fear that at least some white officers feel when seeing a young black, but Dunn hasn’t taken that half-step. Instead, he’s thinking it might be best for police to work with people from the poor communities, who could serve as liaisons in understanding and negotiating the neighborhood.

Oglesby, the retired editor, says the key is the officers themselves, not their racial background. As a young reporter who started on the police beat in St. Petersburg, he says he quickly learned “there are good cops and bad cops.”

He believes the key is selecting the right kind of people to be officers, giving them proper training, and holding them accountable. “Too many have the attitude that the police can do wrong.”

Oglesby says videos are shining a new spotlight on what has been a longtime problem. “The new wrinkle, obviously, is the cellphone camera. The old is the culture of law enforcement, which hasn’t changed much.”

Ken Harms, the former Miami police chief, believes police execs need to go beyond selection and training. They need to manage officers properly — and discipline bad behavior.

He says that far too many times, politics, bureaucracy and the police union prevented him from firing officers who didn’t belong on the police force.

“So it can be easier for a police department to let an officer resign, rather than be terminated,” says Harms, meaning that officer might get a new job in a nearby police department. He says state police organizations need to more active in decertifying bad officers so they can’t work anywhere.

MIAMI VS. BALTIMORE

Dunn notes Baltimore was “less a race riot and more of a police riot.” While Miami’s eruption was bloody with blacks targeting whites, Baltimore had many peaceful demonstrators, including white protesters. The mayor, police chief and top prosecutor are all black. Three officers arrested were black, three white. “There were not large, widespread riots in Baltimore.”

Baltimore’s leaders have asked for federal intervention in their police force. Harms believes that could be a disaster. He says two consent decrees between Miami and the feds while he was chief led to highly restrictive hiring practices – needing to pick from minority applicants who lived within the city limits. That led to a crop of bad young officers, including the notorious Miami River Cops, who used their uniforms to rip off drug dealers.

Harms thinks the current intense focus on cops means officers everywhere are likely to be more cautious. “If they’re more afraid of repercussions from a shooting,” Harm says, they will tend to avoid rushing to “hot calls,” knowing the first two minutes are likely to be the roughest confrontation “between police and the bad guys. So they take the long way around, and arrive 10 minutes later.”

Lawrence, the former county police spokesman, says it’s the job of police to protect and serve communities, regardless of any outside factors. “When you put on the uniform, you should be able to to the job. I don’t care what color you are.”

After the 1980 riots, changes were made in dealing with poor black areas – and to a degree, they worked. Five years later, Simms at the community relations board told The Miami Herald: “The whole police method has changed almost 100 percent. The police no longer go into the black community like occupational forces in alien territory. They deal hard with the criminal element, but with respect for the community.”

Lawrence says after 1980 county cops made changes “not just in personnel, but in approaches. That’s not to say there are not still problems. But it takes some significant event to highlight a problem – and I think that’s what’s going on in Baltimore and in Ferguson.”

To bring it closer to home, Miami Beach police announced last week an investigation into 16 officers who exchanged racist emails.

Meanwhile, Liberty City and Overtown are mired in 1980 decay. Oglesby, the retired editor, points out that’s especially troublesome because in the past 35 years Miami has seen a huge building boom: Not only Brickell and South Beach and downtown Miami, but also once faded poor neighborhoods like Wynwood have seen a huge surge in developer interest.

“There’s been this amazing transformation in so many places,” Oglesby notes. “Liberty City and Overtown are really stuck.”

Why is that?

Leave a Reply